Pan-Africanism part 2: Independence and Neo-Colonialism.

Introduction

In Part 1, we looked at the development of the pan-African movement during the 20th century and how its earlier leaders, such as Henry Sylvester Williams (1869-1911) of Trinidad and W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) of the USA who were part of the African diaspora were more concerned with combatting the horrific racism of the period rather than fighting for African independence.

In South Africa, the South African Native National Congress (SANNC formed 1912), which became the African National Congress (ANC) in 1924, was, in its early days, expressing its loyalty to the British Empire, singing ‘God Save the King’ at its meetings ― even telling the British, “We are more loyal to the Empire than the Boers” (white Afrikaners) ― the message of Native Life in South Africa (1916) written by Sol T. Plaatje (1876-1932), the first Secretary-General of the SANNC.

Even Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), a Jamaican residing in the USA with his emotive populist ‘Back to Africa’ movement, cannot really be understood as having any practical programme for African independence.

The conditions were not there in the early days. Two events changed the landscape.

Firstly the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917 and the formation of the Communist International, the Comintern, in 1919 laid the foundation, attracting and training the most advanced Africans in the revolutionary ideology of Scientific Socialism in preparation for the anti-imperialist struggle.

Secondly - and more importantly - the victory over fascism in the Second World War created an environment for African independence.

The 5th Pan-African Congress in 1945 was preparation for independence.

North Africa

Previously, pan-Africanism had essentially been a reaction to the racism shown to black Africans and those of African ancestry by European colonisers. North Africa was generally understood to be part of the Arab world and of the Mediterranean world.

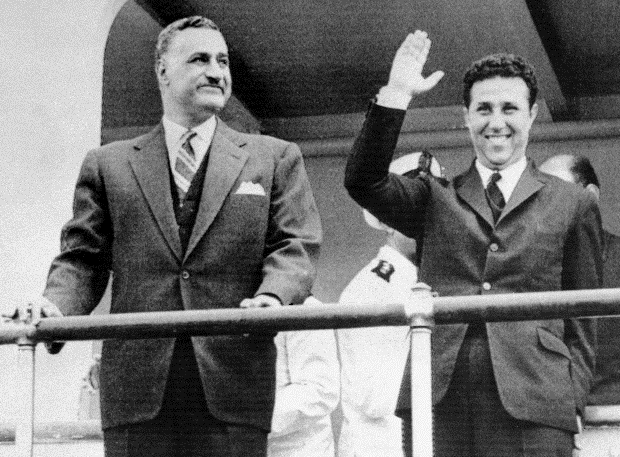

This was to change with the overthrow of the British-supported monarchy in Egypt in 1952 in a coup led by Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser (born 1918) who became President of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser had a huge influence on both Arab nationalism and militant pan-Africanism.

The National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria led by Ahmed Ben Bella (1916-2012) began its liberation war against France in 1954, a war which was to end with Algerian independence in 1962. Algeria had been colonised by France from 1830 onwards, and Europeans, mainly French formed a considerable part of the population. Almost all of them, more than 1 million, left at Independence in 1962 at which time they formed around 15% of the population.2

Ahmed Ben Bella was President of Algerian from 1962-1965 when he was overthrown by a coup within the FLN led by Houari Boumédiène (born 1927) who then remained President until his death in 1978. Despite the coup, Boumédiène carried out similar policies of nationalisation of major industry and giving training for armed struggle to African liberation movements.

Pan-Africanism became a continental rather than a racial movement.

The first arms used in the Zimbabwe liberation struggle were given by Nasser to Joshua Nkomo, leader of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) in 1962; these arms were then smuggled into the country. Later that year, the car carrying many of these weapons was stopped by Rhodesian police and the driver, Bobylock Manyonga was arrested and badly tortured but refused to disclose the origin of the arms. He was then given 15 years imprisonment. Nasser also assisted

Kenya

In 1952, the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), otherwise known as Mau Mau rose up and started killing white farmers and their families in the area known as the ‘White Highlands’ in western Kenya. 32 settlers were killed. This produced outrage by the British. This territory had been identified as a good place for white settlement; it had fertile land and, due to its elevation, a mild climate. It had been systematically cleared of its African population between about 1893 and 1905. This task was done brutally. Village after village was burnt down ― according to the diaries of British officers. In some villages the entire population was slaughtered. Everywhere, livestock, the source of sustenance, was stolen. There is no way of knowing how many tens of thousands were killed deliberately and how many more died of starvation and other indirect causes.

The response by the British was brutal. The leader of the KLFA, Dedan Kimathi (born 1920), was captured in 1956 and hanged in 1957. Around 20,000 Mau Mau were killed, 1090 people were hanged and many more tortured. The herding of people into ‘enclosed villages’ and concentration camps killed maybe 100,000 more. By 1956, the KLFA uprising had essentially been defeated, but small groups of fighters remained until after ‘independence’.

In 1963, Kenya was granted ‘independence’ with Soviet-trained Jomo Kenyatta (born 1897) as its first Prime Minister (under the British crown) and from 1964 as President until his death in 1978. However despite his background, colonial and imperialist relations of production remained. What remained of the KLFA was supressed and its importance in the Kenyan liberation struggle never acknowledged until 2003 under the progressive presidency of Mwai Kibaki (1931-2022; President 2002-2013).

The armed liberation struggle in both Algeria and Kenya led to the two main colonial powers in Africa, France and Britain looking for a new way to keep control of the vital raw materials in their colonies. The tide of African nationalism could not be stopped, instead, it had to be diverted.

Neo-Colonialism

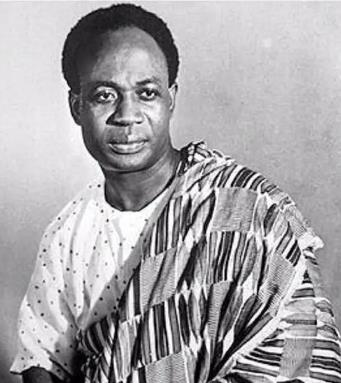

The first recorded use of the term neo-colonialism was in a resolution of the 3rd All-African People’s Conference (AAPC) held in Cairo in 1961. These Conferences held in 1958, 1960 and 1961 can be seen as the link between the Pan-African Congresses, the last, the 5th, which had been held in Manchester in 1945, and the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. Almost certainly, the term was coined by Kwame Nkrumah who later wrote the important work Neo-Colonialism the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965).

Simply stated, neo-colonialism in Africa means, “You can have your black President, national anthem and national flag. We will continue to control your economy.”

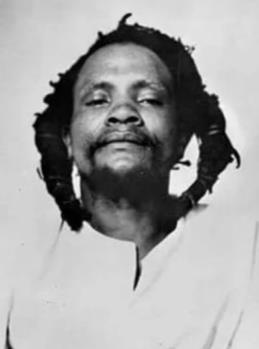

Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) a native of the French Caribbean island of Martinique, was a psychiatrist by profession and went to work in Algeria where he joined the FLN. He had this to say in the chapter ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness’ in his famous book The Wretched of the Earth:

“The objective of nationalist parties… is… strictly national. They mobilize the people with slogans of independence, and for the rest leave it to future events. When such parties are, questioned on the economic programme of the state that they are clamouring for… they are incapable of replying, because, precisely, they are completely ignorant of the economy of their own country.

“In underdeveloped countries, we have seen that no true bourgeoisie exists; there is only a sort of little greedy caste, avid and voracious, with the mind of a huckster, only too glad to accept the dividends that the former colonial power hands out to it. “This get-rich-quick middle class shows itself incapable of great ideas or of inventiveness. It remembers what it has read in European textbooks and imperceptibly it becomes not even the replica of Europe, but its caricature.”

During the 1960s both Britain and France gave ‘independence’ to numerous countries in Africa and the Caribbean, but their economies stayed firmly in the hands of imperialist monopoly capital while the ‘leaders’ lived a luxurious lifestyle. As much as Fanon’s statement was true and remains true today, it is necessary to say that whenever in Africa we have a good leader ― or even a reasonable leader ― the forces of imperialism will block him, remove him from power, or, most frequently ― murder him. In 1960, Belgium gave independence to their huge colony in central Africa, the Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

How little Belgium gained this massive territory at the Belin Conference is another story in itself. It is sufficient to say that the Congo Free State became the personal property of King Leopold II of the Belgians in 1885, this lasted until 1908 when the scandal of forced labour to collect wild rubber was made clear to the world.

It must be said here that the history of Congo is by far the worst in Africa. It is the victim of its own natural wealth. Millions have died.

In 1960 Belgium granted independence to Congo without proper preparation. At the General Election held in May of that year, the Congolese National Movement (MNC) led by Patrice Lumumba won the biggest vote in the new parliament, but as it did not have an overall majority, it was forced to lead a coalition. There were complex negotiations and on 30th June 1960 the Republic of Congo (as it was known then) became Independent. Patrice Lumumba became the first Prime Minister and it was agreed that Joseph Kasa-Vubu should become the ceremonial President. Very soon after his election there was a revolt in the para-military police force against the white officers who remained in charge and the copper-rich southern province of Katanga broke away through the connivance of the Belgian mining company Union Miniere which installed Moise Tshombe as President of Katanga. Belgian troops invaded.

Lumumba travelled to New York to ask for assistance from the United Nations which sent in troops as a ‘peace-keeping’ force. While he was there he also asked for support from the USA but was refused. Lumumba then turned to the USSR which sent in trucks and military advisers. But the USA, Belgium and the UN were in alliance and on 14th September, a coup was staged by the army commander, Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later to call himself Mobutu Seses Seko) who was under the instructions of the USA. Lumumba fled but was captured and later humiliated in front of UN troops which he had called for. Patrice Lumumba was then flown to Katanga where on 17th January 1961 he was murdered. His body was dissolved in acid provided by Union Miniere. A Belgian soldier kept one gold tooth which was returned to Congo in 2020.

The Belgians, the British, the US and the UN were all complicit in the murder. This murder prepared the ground for all the subsequent wars and destabilisation of Congo, still going on to this day. Patrice Lumumba was the first senior African leader to me martyred, other were to follow.

Organisation of African Unity

Formed on 25th May 1963, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was the successor to the Pan-African Congresses and the All-African People’s Congresses; the Founding Conference was held in the shadow of the murder of Lumumba, the continuing conflict in Congo and the beginnings of armed struggle in the south of the continent - Africa was far from free of imperialist interference and control.

There were three different ideological groups represented at the Conference which took place in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital:

- The Casablanca Group: so called because it had met in the Moroccan port city of Casablanca in 1961, was strongly supported by Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea, Modibo Keita of Mali and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt; the group also included Morocco, Algeria and Libya. This group advocated for a United States of Africa and for full continental integration as soon as possible.

- The Monrovia Group: so called because it met in the Liberian capital Monrovia, also in 1961 consisted of Nigeria, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Liberia, Sudan, Togo, and Somalia’ Leaders like Abubakar Tafawa Balewa of Nigeria and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania were supported African unity, but felt that Nkrumah was pushing too hard too fast.

- The Brazzaville Group: had met in 1960 in Brazzaville capital of former French Congo, sometimes referred to as ‘Little Congo’. This group represented most of the sub-Saharan Francophone countries and due to the conditions for ‘independence’ imposed by France, represented French interests inside the OAU, something which was to have a negative impact even after the formation of the African Union in 2002.5

Between 22nd and 25th May 1963, delegates from 32 African countries attended came together and formed the Organisation of African Unity. The 25th May is still celebrated throughout the continent as Africa Day. The compromise agreed to was that the organisation would proceed, step by step to work towards a Union of African States. More than 60 years later we are still very far from achieving that vision, but yet the spirit of pan-Africanism has recently has re-awakened.

In February 1966, just under 3 years later, the main visionary behind the formation of the OAU, Kwame Nkrumah, was removed from power through a coup organised by the British with assistance from the Americans and the French. He was outside Ghana visiting socialist countries at the time ― this, of course, they did not like. But Nkrumah’s biggest crime in the eyes of the imperialists was trying to build an independent aluminium industry based on Ghana’s abundant bauxite (aluminium ore).

Any attempt by an African country to build its own heavy industry based on its own natural resources had to be stopped!

In Part 3 of this series we will look at the total liberation of Africa from direct colonial rule and in greater detail at ‘Françafrique’, the ‘special relationship’ of France with its colonies with an enormous benefit to France, reducing Presidents in Francophone Africa to little more than colonial governors.

Ian Beddowes, Editor