The Birth of Pan-Africanism: Ian Beddowes

I remember around 20 years ago in Zimbabwe telling people that I was a Communist and a pan- Africanist. People laughed, saying that Communism died with the Soviet Union and that African countries were no longer interested in pan-Africanism as the liberation struggle was over and the ruling elites were concentrating on self-empowerment and personal wealth accumulation. Sometimes it is necessary to grit your teeth and stand your ground.

The Soviet Union is no more, but Russia, through both the infrastructure and the social traditions inherited from the USSR, is strengthening economically, militarily and socially, not least due to its response to the war forced upon it by the arrogance and ignorance of the US leadership and its NATO allies.

The deterioration of Western domination, already suffering from the long-term weakening created by the adoption of neo-liberal and monetarist economic policies since the 1980s, has now been considerably hastened by a US President suffering from senile dementia followed by another who has distinguished himself by turning reactionary sloganeering into actual policy.

The fall has already started, the only question is, “How long before the inevitable crash?”. This major shift in the global balance of forces is already being reflected in Africa.

Africa

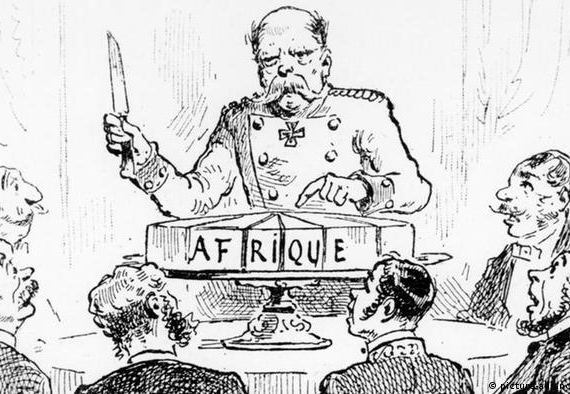

To understand Africa, it is necessary to understand the history of first of slavery then of the partition of Africa following the Berlin Conference of 1885. Slavery, of course, had been a feature of many societies for thousands of years. But the colonisation of the American by Spain, Portugal and Britain from the end of the 15th century created the demand for hard unskilled labour for the mass production of sugar, tobacco, coffee and later cotton.

The source of this labour was Africa; the slave trade.

For Britain in particular, which by the end of the 17th century had developed mercantile capitalism more than any other nation, the slave trade and the establishment of slave plantations in the Caribbean, gave the super profits needed for the establishment of the industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century, (the looting of India by the British East India Company was another major contributing factor). Other European nations followed the example of Britain. The need for new outlets for the investment of capital together with the need for raw materials led the capitalist states of Europe to divide Africa at the Berlin Conference in 1885. Trading ports had been established around the African coast by different countries over the previous 200 years and in South Africa, a few white settlers had ventured inland. Using these established trading stations as a guide, men, who, for the most part had never set foot in Africa, drew lines on a map, which to this day serve as the basis for the modern borders between African countries.

Those borders frequently divided land inhabited for centuries by a particular ethnic group and they often found themselves within the same borders as their traditional rivals. By 1900, only feudal Abyssinia, the British semi-colony of Egypt, the US semi-colony of Liberia and the Afrikaner republics in South Africa were in any way independent.

In many places, Africans resisted the invaders, but spears were no match for the recently invented machine gun. A new form of resistance grew up, not from the traditional leaders, but from people of African slave descent in the Americas and young Africans who became part of the new system in Africa itself.

Pan-Africanism, the Beginning

In Britain in 1897, a lawyer from Trinidad, Henry Sylvester Williams (1869-1911), a writer from South Africa, Alice Kinloch (nee Alexander, 1863-1946) and a lawyer and politician from Sierra Leone, Thomas Josiah Thompson (1867-1941), came together in London to form the African Association to:

“…promote and protect the interests of all subjects claiming African descent, wholly or in part, in British colonies and other place, especially Africa, by circulating accurate information on all subjects affecting their rights and privileges as subjects of the British Empire…”

In 1900, this group organised the First Pan-African Congress in London, changing their name from ‘the ‘African Association’ to the ‘Pan-African Association’. It was a polite affair attended by 30 delegates including the Anglican Bishop of London. One very important young man from the USA was among those who attended ― this was W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963). His name was pronounced in the American style ‘Doo-Boyz’, Du Bois was born into a well-off black family in Massachusetts, he was a brilliant historian becoming the first black American to obtain a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Most importantly, he was to take over the leadership of the Pan-African movement from Henry Sylvester Williams.

At first Du Bois was an elitist believing in the leadership of the ‘talented tenth’ of the black population. His most famous book The Souls of Black Folk, written in 1903 was a proclamation of the humanity of people of African descent in a land where they were ill-treated and despised. Early pan-Africanism was a plea for inclusion into the system. What was later called ‘Black Consciousness’ was necessary for people to regain their self-W.E.B. DU BOIS respect: ‘Black is Beautiful’ was the phrase which spread the message. In the programme of the Zimbabwe Communist Party, Completing the Liberation of Zimbabwe [para 14] it says:

“‘Black Consciousness’ is, without any doubt, important in developing the self-respect of and people of African descent dehumanised by slavery, colonialism and the colour bar, but it can never, in itself, constitute a political programme for the capture of state power by anti-imperialist forces led by the workers and peasants and the subsequent development of production through the promotion of national democratic and socialist economies.”

Following the First Pan-African Conference of 1900, there was no other international gathering until the First Pan-African Congress of February 1919 organised by W.E.B. Du Bois in France four months after the end of the First World War. Blaise Diagne (1872-1934) of Senegal attended, thus including Francophone Africa into the movement. There were 55 delegates from 15 countries with the biggest group being African-Americans. There were 3 more Congresses in 1921, 1923 and 1927. Although there were hints of anti-imperialism during this period, the emphasis was on co-operation and integration of Africans into the system. The movement at this time tended to be intellectual and academic in character.

Marcus Garvey and Garveyism

During this period a new form of populist pan-Africanism grew up under the leadership of Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), a Jamaican. In 1914, Garvey launched the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Jamaica. In 1916, he moved to Harlem, New York, the growing centre of black culture in the USA. By 1920 the UNIA organised the First International Conference of the Negro Peoples in Harlem. An estimated 25,000 people assembled in Madison Square Gardens. At the conference, UNIA delegates declared Garvey to be the Provisional President of Africa, charged with heading a government- in-exile that could take power in the continent when European colonial rule ended. At its height, the UNIA claimed 2 million members stretching across the USA, Caribbean and West Africa. Although this figure is exaggerated, the UNIA was definitely a mass movement. Garvey preached segregation and the building of separate black businesses. In 1922 Garvey met with the Ku Klux Klan on the grounds that they also believed in racial separation. This lost him considerable support.

Garvey was successful in raising large amounts of money for grandiose business ventures but was not adept at accounting or running those businesses. In 1923 Garvey was brought to court for fraud, was found guilty and served two years imprisonment before being deported to Jamaica.

The Comintern and Africa

The Communist International (Comintern) was formed in 1919. During the 1920s it began to take a serious interest in Africa. In February 1927, the Comintern founded the League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression at a Conference in Brussels, Belgium. It was attended by two delegates from South Africa, James La Guma (1894-1961) from the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and J.T. Gumede (1867-1946) from the African National Congress (ANC). Gumede was to become the first militant President of the ANC, serving in that office from 1927 till 1930. As a result of their interaction, in 1928 the 6 Congress of the Comintern adopted a resolution:

“…the Communist Party of South Africa must combine the fight against all anti-native laws with the general political slogan in the fight against British domination, the slogan of an independent native South African republic as a stage towards a workers’ and peasants’ republic, with full equal rights for all races, black, coloured and white.”

And to achieve this goal:

“The Party should pay particular attention to the embryonic national organisations among the natives, such as the African National Congress. The Party, while retaining its full independence, should participate in these organisations, should seek to broaden and extend their activity. Our aim should be to transform the African National Congress into a fighting nationalist revolutionary organisation…”

This resolution was to have far-reaching consequences for South Africa.

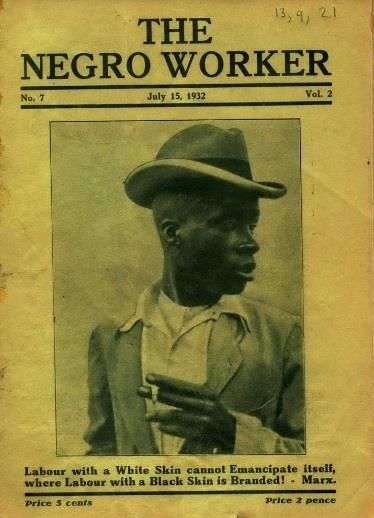

In 1939 Moses Kotane (1905-1978) became General Secretary of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), being responsible for its transformation into the underground South African Communist Party in 1953 d uring the dark days of apartheid. Kotane had been trained by the Comintern in Moscow in the early 1930s. For a long time Kotane also held the post of Treasurer-General of the ANC and has often been referred to as “Chief Architect of the South African Struggle” In 1930, the Red International of Labour Unions, also known as the ‘Profintern’ launched the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers. This body was to play an important role in fostering the trade union movement in Africa.

5th Pan-African Congress

The end of the Second World War came in 1945 with the Victory in Europe coming in May and the Victory over Japan coming in August. In October 1945, the 5th Pan-African Congress was convened in Manchester England. There were 90 delegates. It pulled together all the strands of pan-Africanism, but the victory of the Red Army and the bravery of the Communist-led partisan forces in several countries impressed everyone.

The formerly elitist veteran W.E.B. Du Bois, had, over the years, moved increasingly closer to Communism. Now aged 77 he played a prominent role in the Congress. The main organiser of the Congress was Comintern-trained Trinidadian trade unionist George Padmore (1903-1959). Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), a staunch scientific socialist, was to lead Ghana to Independence in 1957 and to play a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. Also there were Jomo Kenyatta (1897-1978) who was to become the first President of Kenya and Hastings Banda (1898-1997) of Nyasaland who was to become President of independent Malawi.

After the 5th Pan-African Congress the movement for the independence of Africa gained momentum.

Continued in part 2.